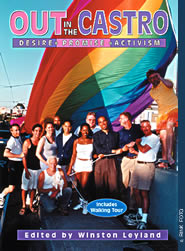

| Excerpt from Out in the Castro Desire, Promise, Activism Edited by Winston Leyland EVERYBODY NEEDED MILK by Anne Kronenberg |

|

||||

| Each time I close my eyes the images of Harvey Milk blur like a kaleidoscope of colorful memories. I knew Harvey for only 17 months and yet that brief moment in time changed my life. Twenty-three years later I still find it difficult to relive my "Harvey days" because they inevitably lead to a familiar feeling of loss and sadness. November 27, 1978 will never be erased from my mind, but I hope through the introspection of writing this essay that I will be able to move past the eulogies and share my memories of the genuine Harvey Milk. | |||||

|

|||||

|

THE CAMPAIGN

|

|||||

|

At age 24 my dream had come true. I was all grown up and living in San Francisco. Unfortunately, my days were spent typing invoices and making coffee for the boss. In late July 1977 my home phone rang. "Hello, this is Harvey Milk," a voice said. I was stunned. I had seen Harvey Milk on Castro Street. I had been to his camera shop-- Castro Camera--but I didn't personally know Harvey Milk. Harvey had run for the Board of Supervisors and had almost been elected to the State Assembly. Everybody knew Harvey Milk, but I had yet to meet him personally. Harvey Milk was a famous person, what reason would Harvey have to call me? Harvey asked if I could come over to Castro Camera to meet him. He

said that my friend Ken Lester had sent him a campaign contribution

and suggested that he talk to me. I hung up the phone and called Ken

immediately. Ken said he'd always supported Harvey, that he knew Harvey

needed good workers, and he knew I hated my job. I hopped on my motorcycle

and flew over to the camera shop. Harvey emerged from the back of the shop with authority. He was charming. His presence was captivating. In retrospect I realize that the effect he had on me was not unique. Many people were attracted to Harvey and responded to his charisma. He was a passionate person and fueled passion in others. I learned that people either loved Harvey or they hated him. His strong personality made it hard to find any middle ground. I wanted so much for him to like me. Harvey walked me to the back of the shop, hidden behind the curtain. The place was cluttered, dirty and dim. The only furnishings were an old wooden desk and some folding chairs. A map of District 5 hung next to the desk. "This, Anne, is my campaign headquarters. This is where it all happens. The seat of power," he offered proudly, smiling one of his famous gotcha-smiles. Because most of my political activity had been in the "bare bones" women's movement, the place looked fine to me. "What I need right now is a campaign coordinator. Ken Lester tells me you would make a good one." We talked for hours. I told Harvey that I had no experience. He told me that he wanted someone young and bright, not a politically seasoned coordinator. Harvey knew how to run the campaign, he wanted somebody to do the daily work, someone he could teach and direct. No one managed Harvey Milk. I learned that even coordinating Harvey would prove to be a huge challenge. Harvey told me that he couldn't pay me, but that somehow he would manage to feed me and pay my $I 00 a month rent. "By the way, I yell a lot. So if you and I are going to work successfully together, you're going to have to learn to yell back," Harvey told me. Then he added, "I need you here by 7:30 or 8 in the morning. Seven days a week. Most days you'll be working 10-12 hours." Besides room and board, the only other promises he made were these: "You'll learn a lot and you'll have a great deal of fun." He was so right. I quit my job and went to work for Harvey the very next day. I never doubted that we would run a successful campaign. I was a believer,

full of enthusiasm and energy. Each person who walked into the shop

was greeted warmly and put to work. Harvey knew everyone's name and

something about their personal life. This is something I learned quickly.

It was a personal campaign, friendly, warm and inviting. What we lacked

in money and equipment, we made up for in good will and fun times. Who the hell was Anne Kronenberg, and why did Harvey bring her into

the campaign? Harvey's former campaign manager, John Rychman, had suffered

a personal tragedy, losing his lover to cancer. Everybody loved John,

and by some I was viewed as trying to usurp his role in the campaign.

Others close to Harvey viewed me as a "spy," perhaps sent

by one of the other campaigns to find out what Harvey was really up

to and to uncover all his secrets. Still others found it odd that Harvey

would bring a woman into the campaign. What could he be thinking? Shouldn't

the campaign coordinator be a gay man? The lesbians in town were in

an uproar because here I was, a self-proclaimed dyke, working for a

man. Surely a traitor to the feminist cause. My first assignment in the campaign was to go shop to shop in the Castro

area and ask storekeepers to put up a Harvey Milk Supervisor/ 5 poster.

It was an eye-opener. My candidate, my hero was not liked by everyone

on Castro Street. A few of the older shopkeepers yelled at me. Others

were plain rude. One storeowner in particular responded to my request

with, "We sure as hell don't need some faggot in City Hall, they

are already ruining Castro Street." My morning walk had yielded

six new signs in store windows. I was disappointed because I felt I

should have been more convincing and gotten signs in every window. Dejected,

I walked back to headquarters, fearful of Harvey's reaction. "Way

to go Annie," he declared. "Six new signs, six new locations."

This was the first lesson I learned from Harvey Milk, he had a "half

full" kind of mentality rather than a "half empty" one. Once I planned a huge fundraiser for Harvey that lost money. I was

very upset and worried that Harvey would be furious. But, as so frequently

happened, he surprised me. "It's the spirit of the event, not the

money we lost," Harvey replied philosophically. Lesson number two,

Harvey was tolerant when he knew you had done your very best. My happiest memories of Harvey are all during the campaign. Harvey would leaflet the bus stops in the morning, then bring sweet rolls into his shop feeding all of his campaign workers and his insatiable sweet tooth. Harvey and I would use the early morning hour to catch up on the campaign, gossip, or just exchange bad jokes. Good times. As a populist, Harvey believed you won an election one vote at a time. We held two or three coffees a week. Some of them yielded new campaign volunteers, sometimes we raised a few dollars, but Harvey explained the most important part of the coffees was meeting people. Every hand Harvey shook was a potential vote. Lesson three, people were more important than money and every person was a vote. As a campaigner Harvey had limitless energy. He scoured the street comers, the bus stops, talking and listening. Harvey walked every precinct in his district. Campaign volunteers covered every precinct too. By the end of the campaign we had delivered two separate campaign brochures by hand to every resident of District 5. In the last two weeks of the campaign we used Cesar Chavez's human billboard concept. Starting at 6:15 a.m., fifteen or twenty of us would hold Harvey Milk signs on Market Street and shout and wave at passing commuters. Motorists loved the human billboard. The more we waved, the more people honked, the more I knew we would win the campaign. Election night was electric. Most of the night is a blur in my mind,

but I do remember the euphoric feeling of victory. Harvey had won 30%

of the vote out of a field of 16 candidates. Harvey was now "Supervisor-Elect

Harvey Milk." The thought was intoxicating. The only vivid recollection

I have of that chaotic night was a surprise announcement Harvey made

during his victory speech. ". . . and Anne Kronenberg will be coming

to City Hall with me as an aide." I was speechless, how could so

many wonderful things all be converging at one time? City Hall would

never be the same again. At that brief moment in time I was happier

than I had ever been in my life. Then I saw my new office space. Ten aides stuffed into a little room separated by partitions. So much for walls, so much for paintings. Dick and I shared a cubicle in a room with the aides for Supervisors Feinstein, Dolson, Silver and Hutch. The Supervisors had offices across the hall from us. How could we conduct business sitting next to our political adversaries? At this point I didn't understand the importance of building bridges with those who were not naturally your political allies. Somehow I thought we could magically make changes occur just by doing what was right. In our cubicle, you could hear everything anybody said or did. We had precious little space and no privacy. We soon got to know the other aides and formed close alliances, in spite of the fact that our bosses often stood on different sides of a political issue. During Board meetings we had the "squawk box" on so we could all listen to our bosses as they pontificated. Often one of us would start yelling at the box telling the offending Supervisor to sit down and shut up. I'm sure the Supervisors would have been appalled to hear us, but, on the positive side, it brought us all close together. We had our fun too. After a few months at the Board, we established an aides' bulletin board called "letter of the week." We would have competitions every week to see which office had received the craziest correspondence. Our office always won. Any glamorous illusions I had about coming to City Hall were quickly dispersed. I learned that the job was difficult, often thankless and always frustrating. Everybody thought we could solve their problems whether it was cars parked on sidewalks, dog poop in the park or street signs that needed repair. We were district representatives and Harvey was elected to handle these problems, to be the voice of District 5 in City Hall. Each morning Harvey would empty his pockets stuffed with scribbled napkins filled with names, numbers and constituent problems. More work for Dick and me. It was tough, the phones never stopped ringing, constituents never stopped dropping in to lodge complaints, and most evenings were filled with district meetings. There was so much to learn, and no time to learn any of it. We were constantly bombarded with requests and demands. Dick and I weren't the only ones who felt frustrated. Life at City

Hall was not as Harvey had envisioned it either. It was one thing running

a campaign, it was quite another working within the bureaucracy to accomplish

your goals. Harvey, the unstoppable campaigner, now applied that energy

and zeal to City Hall. He went 18 hours a day. Some nights he would

attend 4 or 5 different events. He never stopped. I felt bereft; I never

got to see him anymore. City Hall was very different than the campaign.

From my perspective, it was harder being on the inside than it had been

being on the outside. The old Supervisors, those who had been around prior to District Elections, were not thrilled with the new kids on the block. There was a certain etiquette that should be followed at City Hall. One should not come to work in jeans, or, worse yet, boots and leather jacket. One should definitely not come to work on a motorcycle. One should always address the Supervisor with their earned title, one never called a Supervisor by the first name, especially someone as lowly as an aide. One day I was walking toward my office, in my raingear (because it was raining and I rode my motorcycle to work) hand in hand with my lover. We turned the corner just in time to run head-on into Dianne Feinstein. By the expression of horror on her face, I knew she was appalled. Harvey found the story terribly amusing. Much later Dianne recalled that scene and my impropriety, but in her version I was dressed in full leather. Harvey didn't give a hoot about any of these things. In fact, Harvey reveled in the fact that we were making people uncomfortable. Harvey took great pleasure in saying the words "dyke" and "faggot" in meetings with other elected officials, who generally found this less than amusing. If Harvey was attempting to shake up the establishment, he did it with glee. Harvey was gutsy, shrewd and courageous. Politically he knew how to strategize, lobby his colleagues and sponsor successful legislation. He spoke about uniting all minorities, people of color, youth, women, elders, gay and straight. If we all united we would no longer be the minority. It was a time of great hope, an exciting, inspirational period. Times were changing, you could feel it. During his brief tenure on the Board, Harvey was successful in authoring the Gay Rights Ordinance and getting it signed into legislation. He also authored the Pooper- Scooper Ordinance. "Whoever solves the dog shit problem in this city will be elected Mayor," Harvey prophesied. With the advent of District Elections, odd number districts were granted 2-year terms and even number districts 4-year terms. Harvey needed to begin his next campaign immediately. He began garnering support for his reelection. The first stop was soliciting all those who had opposed him in the past. By late summer, Harvey's list of endorsers included Congressman Phillip Burton, Congressman John Burton, Assemblyman Art Agnos and Mayor George Moscone. Harvey was in his element. He may not have beaten the MACHINE before, but now he was playing hardball with the big boys and they were all backing him. During the "No on 6" campaign, we were all overworked and stressed out. Senator Briggs's Initiative threatened the very fiber of our belief, that all people, regardless of sexual orientation, are equal. Briggs wanted to ban gay teachers in California. Harvey crisscrossed the State campaigning against 6 and debating Briggs. He was never in the office. He was fighting for all our rights. Should we be judged by the color of our skin or by our sexual persuasion? He made people uncomfortable, but he made them look lesbian and gay rights straight in the face and confront their fears. Fall of 1978 was a roller coaster ride, ending in disaster. Harvey's lover Jack committed suicide, we were engaged in the statewide campaign to defeat the Briggs Initiative, and the Reverend Jim Jones mass suicide at Jonestown shocked the very core of the City. We needed a breather; we needed time to regroup. We were never given that time. November 27, 1978, Dan White, a former Supervisor, walked into Mayor Moscone's and then Supervisor Milk's offices and committed an obscene, unthinkable act. He murdered them both in cold blood. My own age of innocence and naiveté came to its own brutal end that day. |

|||||

|

LIFE AFTER THE ASSASSINATIONS

|

|||||

|

Harvey Milk's life and death changed the course of history. His life impacted a generation. For me, Harvey's death changed everything. To survive I had to separate those feelings. I needed to protect myself because the hurt was so intense. I put Harvey in a compartment in my brain. It was safe. I kept him there and brought him out when I felt strong. I have avoided public displays like the candlelight march--it reminds me of the pain, the anger, the rage that someone took Harvey away. I realized when writing this essay that I have put Harvey in a closet in my mind. How funny. Harvey, who talked about breaking through closet walls. In a lifetime you only have a handful of good friends, and I was blessed Harvey was in my handful. He was my friend, my mentor, even a surrogate father. He fueled a passion in so many of us. Harvey was the teacher and all of us campaign workers were his students. I learned everything I know about politics from Harvey Milk. That is why Harvey is still missed and emulated today, because he really cared about people and was so human himself. But a myth has evolved over the past 23 years and his untimely violent death raised him to something akin to martyrdom. What is left out of the myth are the very qualities that set Harvey apart from others, the things that made him a "very real touchable" person. I have this recurring dream. I am walking down the street, it is the present time, and there is Harvey, tanned and carefree. "Harvey, why did you go away, why did you leave? I miss you so much." "Anne, don't worry, I have always been here and will continue to be." "But Harvey, I don't understand, I thought you were dead." Then I wake up and realize he isn't. His spirit is here. His legacy

lives, his life lives on. I consider myself lucky. I knew more of Harvey

than what I have read in books or seen in a movie. Harvey Milk was my

friend. |

|||||